- Like

- SHARE

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Flattr

- Buffer

- Love This

- Save

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- JOIN

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Know Your Meniscus

Know Your Meniscus

Getting injured is not something that we can anticipate nor predict every time we exercise or step into our sport. Knee injuries are common, particularly for contact sports wherein meniscal tears, ACL tears, ligamentous sprain/strains and muscle tears are all too common. And yet, anyone at any age is susceptible to a tear of the meniscus, from the weekend warrior, to the seasoned exercise pro.

So, let’s begin by diving into some of the epidemiology of meniscal injuries, the anatomy of the knee, form versus function, types of meniscal injuries, and supplementation.

Epidemiology

The rate of incidence of meniscal injuries are approximately 60-70 per 100,000 with a male:female ratio of 2.5:4.1. Many documented cases of meniscus-related traumas do not come from sporting events, as commonly thought; although per-capita, when comparing the athlete and non-athlete populations, the incidence rate favors athletes. Partial meniscal surgeries, or minescectomies, are the most commonly-practiced surgical intervention for cases where traditional conservative measures like rehabilitation or strength programs become ineffective.

Anatomy

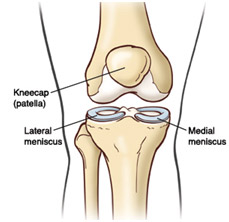

The knee is comprised of the femur (upper thigh bone) and tibia (lower leg bone) and fibula (lower leg bone, lateral side). These bones are end-capped by cartilage, which acts as a protective barrier between the bones (as we age, these layers degenerate, which is when we begin to experience osteoarthritis and DJD). These massive bones are connected by four large ligaments the Anterior, Lateral, Medial and Poster cruciate ligaments. To prevent grinding between these bones we have the medial meniscus and lateral meniscus, two c-shaped shock absorbers comprised of cartilage.

The knee is comprised of the femur (upper thigh bone) and tibia (lower leg bone) and fibula (lower leg bone, lateral side). These bones are end-capped by cartilage, which acts as a protective barrier between the bones (as we age, these layers degenerate, which is when we begin to experience osteoarthritis and DJD). These massive bones are connected by four large ligaments the Anterior, Lateral, Medial and Poster cruciate ligaments. To prevent grinding between these bones we have the medial meniscus and lateral meniscus, two c-shaped shock absorbers comprised of cartilage.

The function of the menisci aid in transmission of the load of the body, aid in stability, shock absorption and provide nutrition and lubrication to the articular cartilage – the tissue that is the ‘end cap’ to our bones.

The medial meniscus (inside of our knee) is connected to the medial cruciate ligament. Due to these attachment configurations, it is less mobile than the lateral meniscus (outside of our knee) and is more susceptible to potential injury, roughly 55 – 60% of the time. ACL tears, when they occur affect and tear the lateral meniscus owing to their structural proximity.

Location, Location, Location: the posterior aspect of the meniscus is the most susceptible to damage. This is so, because most of our load-bearing forces are concentrated there. Injury usually occurs when the knee is slightly flexed, such as in an athletic stance. This position, combined with a sudden twisting motion is what traditionally causes the tear.

Calling Wolverine: Healing Factor: The blood supply of the knee as it pertains to the menisci is limited to the outer third, and has excellent healing potential. The inner two-thirds are not so fortunate, and are where many tears often occur. As we age, the integrity of the blood supply to these regions decreases, which reduces healing potential.

Mechanisms of Injury

Typically, damage to the meniscus occurs as a result of gradual, repetitive wear and tear (i.e. natural degeneration) as well as singular traumatic events. The most common position for a meniscal injury is when the knee is in a loaded position (such as an athletic bend) with torsion (twisting about the knee); or when the knee is in hyperflexion. Lateral and medial impacts (side-collisions) can also rupture the meniscus as well as tear those ligaments.

Typically, damage to the meniscus occurs as a result of gradual, repetitive wear and tear (i.e. natural degeneration) as well as singular traumatic events. The most common position for a meniscal injury is when the knee is in a loaded position (such as an athletic bend) with torsion (twisting about the knee); or when the knee is in hyperflexion. Lateral and medial impacts (side-collisions) can also rupture the meniscus as well as tear those ligaments.

Common signs and symptoms are sustained pain and swelling after a contact injury; medial or lateral knee pain; clicking, popping, locking; and reoccurring swelling of the knee after exercising.

The structural tearing of the meniscus can vary greatly from a small posterior flap-tear, to a semi-lunar continuous tear, or a large flap-tear that folds over on itself. Other most-commons include oblique tears and radial (transverse tears).

Diagnosis

X-ray imaging cannot detect meniscal tears because this type of imaging study shows osseous tissue only, and not soft tissue such as ligaments, tendons, skin and muscle. X-rays are useful however, as an entry-level imaging study to help rule out potential fractures. MRI is the preferred method with medial and lateral meniscus tear detection sensitivity of 91.4% and 76.0%, respectively; as well as medial and lateral meniscus tear detection specificity of 81.1% and 93.3%, respectively.

X-ray imaging cannot detect meniscal tears because this type of imaging study shows osseous tissue only, and not soft tissue such as ligaments, tendons, skin and muscle. X-rays are useful however, as an entry-level imaging study to help rule out potential fractures. MRI is the preferred method with medial and lateral meniscus tear detection sensitivity of 91.4% and 76.0%, respectively; as well as medial and lateral meniscus tear detection specificity of 81.1% and 93.3%, respectively.

Statistically, 16% of asymptomatic knees demonstrate meniscal tearing; while individuals over the age of 45 demonstrate 36%.

Orthopedic tests which feature the patient in a weight-bearing position, as well as stress-tests to the joint line of the knee include McMurray’s test, Apley’s test, Ege’s test and Thessaly’s test.

Outcome

Clinically, it is always best to be evaluated by a health care professional. Traditionally, orthopedic tests are conducted, and if testing is positive, imaging studies are warranted. If the pain persistsphysical therapy or chiropractic care may be deemed appropriate depending on the level of severity of the potential tear. If the imaging study showcases significant tearing, surgery may be performed to repair, reduce, or excise the offending particles.

Clinically, it is always best to be evaluated by a health care professional. Traditionally, orthopedic tests are conducted, and if testing is positive, imaging studies are warranted. If the pain persistsphysical therapy or chiropractic care may be deemed appropriate depending on the level of severity of the potential tear. If the imaging study showcases significant tearing, surgery may be performed to repair, reduce, or excise the offending particles.

Supplement Health

Going forward, either post-surgical or after PT/Chiro care, your body has overcome a massive trauma to key areas in one or both of your knees. While your body heals, it will never be structurally as strong as it was pre-injury.

Going forward, either post-surgical or after PT/Chiro care, your body has overcome a massive trauma to key areas in one or both of your knees. While your body heals, it will never be structurally as strong as it was pre-injury.

The good news however, is that there are ways to offset further degeneration and potential risk for future meniscal tearing by supplementing with the following:

- Fish Oil

- Chondroitin Sulfate

- Glucosamine

- Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM)

- Hyaluronic Acid

For a complete listing of these supplements, see my previous article on Supplementation for Healthy Joints.

References:

1. Belzer, J. & Cannon Jr., W.D. 1993.Meniscal tears: treatment in the stable and unstable knee. J of the Amer Academy of Orthopadeic Surgery. 1: 41 – 47.

2. Fan, R.S.P & Ryu, R.K.N. 2000. Meniscal lesions: diagnosis and treatment. Medscape Orthopaedics & Sports Medicine. 4(2).

3. Johnson, V.L. & Hunter, D.J. 2014. The epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clinical Rheumatology. 28(1): 5 – 15.

4. Kilcoyne, K.G et al. 2012. Epidemiology of meniscal injury associated with ACL tears in young athletes. The Cutting Edge.

5. Leuck, M. 2014. Managing the Meniscus. Dynamic Chiropractic. 32(10): 1 – 25.

6. Mordecai, S.C, et al. 2014. Treatment of meniscal tears: An evidence based approach. World J Orthop. 5(3): 233 – 241.

7. Poehling, G.G., Ruch, D.S. & Chabon, S.J. 1990. The landscape of meniscal injuries. Clinical Sports Medicine. 9(3): 539 – 549.

8. University of Connecticut. 2014. Knee Conditions and Treatment. New England Musculoskeletal Institute. Retrieved from: http://nemsi.uchc.edu/clinical_services/orthopaedic/knee/meniscus_tears.html

About Shannon Clark

Shannon holds a degree in Exercise Science and is a certified personal trainer and fitness writer with over 10 years of industry experience.